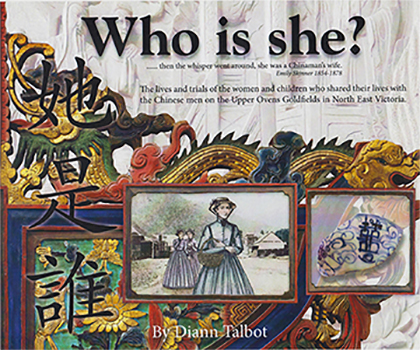

Who Is She?

A sad verse and the name Premetta with no surname, is all that is recorded on the headstone. There had been speculation over the years as to who Premetta was, and these rumours continued until I found a photo in my great grandmother’s album. It was a photo of a beautifully dressed young girl with flowing dark hair, and on the reverse was written,

Dear Premetta, died October 1889, “I heard the voice of Jesus say, come unto me and rest”.

A little research revealed that Premetta was born at Harrietville and was the daughter of Lucy Duke and a Chinese merchant named Ah Hing. Further research revealed that Lucy’s sister, Susannah, was also living in Harrietville and married to a Chinese storekeeper named Ah Yew.

As I delved further into the archives I discovered that there were dozens of young women and girls that had married or lived with Chinese merchants, storekeepers, hotel owners and farmers. Yet virtually nothing of their lives, or existence, has been documented in local history publications, but they were here, labouring under the same hardships suffered by other pioneer women. The burden of pioneering life was often harsher for these women as they were often subjected to undisguised distain from mainstream society, usually due to their choice of husbands. Some, through economic success, were accepted as part of the community.

One of the biggest difficulties in researching this publication has been determining if I have the correct record associated with the person I am researching. Chinese names were usually interpreted by Europeans phonetically and one person’s version of how the given name should be spelt often differed from another. Ah Yew was also recorded as Ah You, Yew, Yews Why Yew, Why Chung You. Ah Moy was spelt a variety of ways. Ah Young could be Chun Young, Ah Yung, Ah Chun Young or just Young, there is a veritable flock of Ah Young’s and it was very difficult to determine which was the “right” Ah Young. Ah Ken, Ken, Kene, Quan Ken, Quan Kee, again so many Ah Ken’s and likewise, Ah Sue, Shuey, Ah Shuey and Ah Shue. There were quite a few individuals with any of the above variations, and more, and sometimes many variations could for the same individual but at various times. I have headed each chapter with the most commonly used name but variations do appear throughout the text as I have used whichever version was used according to the research material referred to in that instance.

Sometimes the children of these Anglo/Chinese unions were sent to China by their fathers, some never returned, some did. Of those that left and never returned, their Australian families often lost contact with them. Occasionally European wives would accompany their husbands back to China but the expectations and traditions expected of a wife were vastly different in China, and most returned to Australia, sometimes having no option but to leave some of their children behind.

Sometimes European grandparents would use their surname if the child came under their care. It was not unusual for foster parents to change a child’s surname to their own. Children with Chinese parentage often went through numerous name changes; often the mother’s maiden name would appear on the birth certificate. Later documents might record the child’s name as the surname of a defacto partner, often changing several times over a period of time.

Children in those situations often had their Chinese ancestry suppressed and the instigators of these name changes would hope that any Chinese heritage would be soon forgotten, but maybe with a grain of optimism, some whispers may have survived through the years. All of this made it very difficult to determine the fate of some of the less fortunate children from these unions, namely the ones that were deemed neglected and committed to institutions.

In a few instances I have been very fortunate to have made contact with some very enthusiastic descendants of several families and through the sharing of research, family stories and photographs the chapters featuring those families give a more detailed account of the lives of those pioneers. Other family descendants were keen to learn about their forebears but due to generations of denial and secrecy there was little that they could contribute. There are many unfinished stories, gaps, dead ends and sometimes the complete and intentional disappearance of an individual. Names were changed, and then came the secrecy and denial.

The story of these women, their children and their Chinese husbands is a story soon to be lost in the crevasse of time, but it is a vital part of our history and a story waiting and needing to be told. Hopefully it is not too late to grapple it back from its plummet into obscurity.